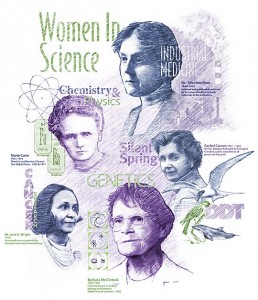

Women in Science (or What You Didn’t Learn at School)

Women have notoriously been more outspoken against war throughout history. Whether it is because the experience of giving life and being a parent as a woman is different or they are just more peaceful creatures by default – the reality is that it’s the case. So today I decided to dedicate a short article about women and tech and science. Yes, it seems not related but it is very much so. And I believe it’s the case because we often underestimate the involvement women have already had in science in general against all odds and thus make it hard for them to continue. And just imagine for a second a world where we equally take part in the technological progress and in any decisions made as a result. I do believe the planet would be a much better place.

So below you will find a very, very short outline of some great characters that have left their imprint on modern day life without most of us even knowing of their existence. Feel free to learn more about them at will – they surely deserve it.

Agnes Pockels, 1862-1935

Agnes never went to college as she wasn’t allowed – at the time few colleges accepted women. Her father and brother both had degrees in physics and she read their books in her spare time between chores such as dishwashing and cooking. She ended up completely self-taught and not only discovered the influence of impurities on the surface tension of fluids but came up with a device (now known as the Pockels trough) that is a key instrument in the new discipline of surface science. Using an improved version of this same thing, the American chemist Irving Langmuir made some additional discoveries and earnt himself a Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1932. Obviously Agnes didn’t get one. What to say.

Emmy Noether, 1882-1935

Emmy’s father was in mathematics. She however struggled (but finally succeeded with persistence) to get a degree. However, she was not allowed to be a teacher – her dream at the time, as the University of Erlangen had a policy against women professors. Whilst studying at University of Göttingen, she met with Felix Klein and David Hilbert. They invited her to join the Mathematical Institute in Göttingen and together began working on Einstein’s general relativity theory. Three years later she proved two theorems that were basic for both general relativity and elementary particle physics. One is still known as “Noether’s Theorem.”

Maria Goeppert-Mayer, 1906-1972

Well, if you paid at least a little attention at school, you would know Marie Curie. Maria was the second woman to win the Nobel Prize in physics and for something rather interesting – she solved the mystery of the magic numbers. The following numbers – 2, 8, 20, 28, 50 and 82 (did someone shout Bingo?:)) – are the number of protons in atomic nuclei. No one knew why these elements were so stable at the time. Maria thought protons and neutrons in the nucleus sit in shells just like electrons and that filling nuclear shells is what leads to stability. She went as far as to prove that nuclei do have shells and do actually form what she called magic nuclei. At those numbers, protons and neutrons arrange themselves into highly stable symmetrical spheres. That all wasn’t as easy as it may sound now, as on top of the struggle to graduate (even with the help of her father who was a professor himself), Maria didn’t have a paid job or an office right until she got the Nobel Prize (greeted by the headlines in newspapers “S.D. Mother Wins Nobel Prize.”, please!) – she ended up teaching and helping for free just to be able to stay around in universities, often following her husband who was a professor too.

Well, that’s for starters and should give you something to think about. Hope you enjoyed this reading and will be back soon for more.